Introduction.

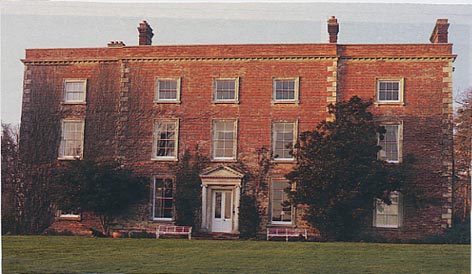

Stanfield Hall is a large and ancient mansion situated about 10 miles south-west of Norwich in the county of Norfolk. From about the 1100s, it was held by Earl Warren and later by the Bigods, Earls of Norfolk in the 1200s. It was, by early Victorian times, the principal residence of one Isaac Preston, Esq, a barrister and chief judge of Norwich. The Prestons were a family of landed gentry long established at their main seat of Beeston St Lawrence north-east of Norwich, near Wroxham. The Rev George Preston of that family had inherited Stanfield Hall just before 1800, when he had it largely re-built at great expense. On his death in 1837, his son Isaac succeeded him there when he was about 50. He had a son Isaac Jnr and a daughter. A drawing shows the Hall in 1829:

The estate Isaac inherited consisted of the large moated Hall, its extensive grounds, a home farm, as well as many other farms and cottages spread over 20 parishes. He was thus very well-off. The home farm was rented out to a neighbouring tenant farmer, one James Blomfield Rush, who also served as the Preston's bailiff. Rush was also seeking to purchase the farm next door, called Potash Farm and to this end had borrowed money from Isaac to assist him in that purchase. That was in late 1838 and the money plus interest was due for re-payment after 10 years - in November 1848. During that interim, Rush and his large family did live at Potash farm.

On the evening of November 28th 1848, just two days before that due date, Isaac and his family, including the younger Isaac and his wife, were having dinner at the Hall. It was Isaac's known habit after dinner to step out onto the porch for a little evening air. Being November, it was rather dark on the porch so that Isaac didn't notice what appeared to be a strangely dressed person hiding in the shadows there. Suddenly, two shots rang out and Isaac fell to the ground, mortally wounded. The others rushed out of the dining room into the hall and were greeted by the same person, who had entered the house. He shot three more times, killing Isaac Jnr and wounding his mother and a servant. The strange figure then ran off into the night, after dropping two hand-written notes onto the floor.

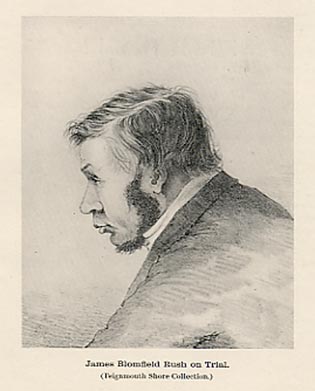

One of the other servants later said that he thought he recognised the profile of the murderer in the odd costume, with a false beard and wig, as that of James Blomfield Rush, the family's bailiff. But it was difficult to be certain. The police soon arrived from Norwich and after hearing accounts of the situation, decided the next morning to arrest Rush and charge him with the murders - being the most probable suspect. He had reneged on previous loans and agreements with Isaac and now his major debt to him was soon due for re-payment. As always, he had no money.

The double murders were of course reported in both the local and national press, some papers running two or three editions on the story each day, as new elements were revealed. Readers did not however read about the murders of the two Isaac Prestons, Snr and Jnr, but of those of Isaac Jermy, Esq, the judge, and of his son Isaac Jermy Jermy, Gent To account for these rather unexpected names, and to provide more of a background to these horrible murders, we must go back in time - a considerable way.

Background.

An ancient family named Jermy arrived in England from Normandy soon after William the Conqueror - by about 1100. They were of the knighted class, holding their estates from various Earls and Barons by 'knight's fees' - mostly in East Anglia. By the 1500s, however, they had acquired freehold ownership of their own properties. One branch of the family settled in north Norfolk and a later son of this line, John Jermy, Esq, became a successful lawyer in London before returning to Norfolk to take up the position of chief counsellor to the Bishop of Norwich - around 1600. He did well in this post and was soon in a position to purchase two estates in north Norfolk for his sons. The elder son, Francis, settled at Gunton Hall, near Aylsham, while the younger one, Robert, did so at Bayfield Hall, near Holt. We discuss these in turn:

(i) The senior Jermy line, at Gunton continued there some generations, until about 1700 - when the estate had to be sold to cover mortgage debts accrued years before, during the civil war, as happened to many. By the late 1680s, the elder son there (a later Francis) did at least attend Cambridge although didn't go on to a career in either the law or the church. After the estate was sold, he settled for a time in Hainford, near Norwich, where he married and had two surviving daughters before abandoning them and their mother for London where he seems to have lived 'on his wits'. He then had three sons there in an irregular 2nd marriage but no later Jermys descended from them - ie into the 1800s. Francis did have a younger brother back at Gunton but he received even less from the estate and very little education. He was in fact set to a working class apprenticeship - in Gt Yarmouth - although did later obtain a slightly better position in the Custom's Service there through the influence of earlier family contacts. He was thus in a position to afford to give his elder son at least, training as a Shipwright but that son died quite young, without leaving an heir. But his younger son obtained neither education nor training (it being too expensive) and was later referred to as 'an illiterate day-labourer'. His name, ironically (considering the family's eminent origin), was John Jermy. It is not known if he ever married or had issue. He died in 1768 in Yarmouth, the sad ending, it seemed, of his (Gunton) branch of the ancient and proud family of Jermy - of landed gentry status since the 1100s.

(ii) The junior Jermy line, at Bayfield, continued there a little longer - until about 1750. By 1735, the senior survivor there (after 5 generations) was a respected Norfolk lawyer and landowner whose only son, William Jermy, Esq, was ready to marry that year. A union was arranged with the only daughter of a wealthy landowner of south and west Norfolk (not the Jermys' usual area of influence) - the Hon. Elizabeth Richardson. She was soon the heir to her family's large estate, including Stanfield Hall. In those times, a husband became effective owner of his wife's property and, as William's father had recently died, he was now in control of both Bayfield Hall and Stanfield Hall, and their estates. Unlike his father, however, he wasn't very good at husbanding his resources and spent most of his time enjoying the lively social, partying scene amongst the landed gentry of Norfolk and in London. They never resided at either Hall but at their homes in Norwich and Aylsham, which were more convenient for their active social life. But he and his wife quarrelled and were soon divorced, she then dying before 1750. They had no children.

William was now free to marry again and would of course be quite a catch with all his wealth. But he too was now quite ill and apparently not very capable of handling his own affairs. It was at this point that a shrewd local lawyer - an earlier Isaac Preston (of the same family as those described above) - 'befriended' him (having worked with William's father previously) and soon convinced William to marry his (Isaac's) sister Frances Preston - in 1751. Conveniently, William himself died very soon after (they probably never lived together) and so had no children. As the last of his family, with no close relatives, his estate was really now in the hands of the Prestons. What would happen now? Who was to get his vast estates? And what did William's Will say? Needless to say, the Will had been drawn up by this earlier Isaac Preston, a clever lawyer. The property was to go to William's new widow, Frances, for her lifetime and then to one or other of two named Preston relatives, and their sons, if any. But these two men both died before Frances (d 1791) and without issue. In that case, said the Will, the property should go "to the male person with the name Jermy nearest related to me (ie to William) in blood, and to his heirs forever".

The 'property' by the time Frances died was however now lacking Bayfield Hall and estate as the Will had also stated that Frances was to receive £5000 from the entire estate during her lifetime. This was much too much to raise from annual rental income so it was decided (by Frances's brother Isaac) to sell Bayfield! This was almost criminal (destroying the capital value of the estate) and certainly smacked of the influence of Isaac in composing William's Will. It was thus sold in 1765 to the Jodrell family for £7600. [Some years later, in 1817, a Norwich weaver named Jonathan Jermy made a claim for the Bayfield estate through the courts based upon a pedigree that appeared to indicate he was a descendent of the Bayfield Jermys and thus William Jermy's nearest heir-at-law. His apparent Jermy forebears over the 4 previous generations did have the very same christian names as did William's, and in the same order, but his claim was made just after the relevant Statute of Limitations had expired and his pedigree was thus never examined in court. This was however later pursued by myself and it was discovered that way back in 1640, Jonathan Jermy's family's name had actually been Jermyn, an unrelated family, but altered to Jermy after the civil war by church Vicars who were more familiar with the name Jermy. This family had actually settled near Stanfield! It was simply a remarkable coincidence.] A later member of the Jodrell family left Bayfield to the youngest son of the Earl of Leicester (to whom he wasn't related, I believe) and in more recent times it came to the distantly related Combe family, who reside there today:

Bayfield Hall (2005)

At least Stanfield Hall was still intact (back in 1791). But who was 'the nearest blood relative of William Jermy - with the surname Jermy - that year? There were no Jermys left in the Bayfield line (Jonathan Jermy's erroneous claim to be of that line was still some years off). What about the Gunton Jermy family - previously dispersed to London and to Gt Yarmouth ? By 1791, none of the London members of that branch were still alive. And in Yarmouth, the last of that family of which we were aware had been John Jermy, the day-labourer described above, and he had also died - in 1768, seemingly without issue. What would happen now therefore? Well, a short time after Frances died, another member of the Preston family (also a lawyer), not mentioned in the Will, quietly walked into possession of Stanfield Hall and instructed the estate's Steward to forward the considerable rental income in future to him (then residing in Kings Lynn), as he claimed he was now the new owner - "being the nearest relative to Frances", as he stated. For this he produced some apparently forged documents by which the earlier Isaac Preston (who had foreseen even this circumstance) had shown that any future rights to the estate that might be claimed by anyone else had been sold - by the last two Jermys then living, for relatively small sums, many years before. It was over 40 years since William's death and his Will was published. Who else would have any knowledge or interest in such a Will by this time? No one apparently. There wasn't it seemed 'anyone else' - to even question that suspicious justification. No one, seemingly, came forward to complain. Stanfield Hall thus remained with the Prestons.

Enter John Larner.

After just 5 years, this latter Preston also died, unmarried, and so left the estate, by his Will, to his younger brother - the Rev George Preston - whom we have already met above. He did move into the Hall, with his wife and family, including his young son Isaac Preston, then about 12. It all appeared quite safe and legitimate by this point. Rev George and wife had one further son, in 1799, whom they christened 'William Jermy Preston' - apparently giving this token nod to a requirements of William's Will that anyone inheriting his estate must bear the name Jermy, assume the Jermy Arms and Crest and never sell his library of old books. But when he re-built the Hall, George had his own Preston arms placed over the front door and neither he nor his eldest son Isaac altered their names to Jermy. He and the family then resided at Stanfield for an untroubled 40 years - until the Rev George's death there in 1837 when eldest son, now Isaac Preston, Esq, inherited, as mentioned earlier. Just to be safe, however, he had previously given his son the name Isaac Jermy Preston. In June of 1838, Isaac Snr decided to re-furbish the Hall before moving in and auctioning off his father's old furniture, etc - including the old books that had belonged to William Jermy. The day of the auction arrived and during the afternoon, two unknown men from London appeared upstairs and looked over the books. They asked to speak to Isaac Preston. Their names were John Larner and his 'adviser' a Daniel Wingfield. This meeting between Isaac Preston and John Larner would, in time, turn out to have dire consequences for both men, and for a third man.

When Preston arrived, Larner calmly informed him that he had "come to take possession of his family's property" - that is, of Stanfield Hall and all its estate - he being "the true heir-at-law"! Preston was quite taken aback by this, having never heard of Larner. And quite possibly his father George had never informed his son of the Preston's suspect acquisition of their property so many years before. It was, after all, almost 50 years since Frances had died and 140 years since William Jermy had done so - his Will having long since remained a dormant artefact, one might well assume. However, Larner quickly informed him that the Will had expressly forbade the sale of William Jermy's library, as well as requiring any who inherited the estate to bear the Jermy arms and to change their name to Jermy, neither of which the Preston's had done. Larner, at least, seemed well aware of the Will and its contents. Being a trained lawyer, Preston advised them to leave the premises immediately and pursue any such claim through the courts in the more usual way. They were reluctant to leave so he had the police escort them off the property.

Isaac must have been impressed with Larner's claim and knowledge of the Will for he immediately halted the auction of the books and of the other items. Within a short time he also replaced the Preston arms over the door with those of Jermy and, in remarkably quick time as well, applied to have his family's surname legally changed from Preston to Jermy which was announced in the official Gazette in London in August that same year (1838). Henceforth, he would thus be known as Isaac Jermy, Esq and his son as Isaac Jermy Jermy, Gent (thus explaining the form of their names as reported after the murders, still 10 years hence). Moreover, as Isaac realised he apparently didn't have a legal title to the property, he decided to sell it - to his bailiff - James Blomfield Rush - for a mere £1000 (a tenth of its true value) on the pretext that otherwise he was going to have it torn down and sell off all the materials. He seemed to realise that Rush couldn't handle money or his affairs very well and sure enough, within the year, he was able to buy it back again at the same price. And now he did have a bill of purchase. It was all quite neat but rather suspect.

The Siege of Stanfield Hall - 1838

. But in the meantime, John Larner, who couldn't afford to go to law on his claim (the basis of which was still a complete mystery), decided to proceed more aggressively. During the rest of that summer, he tried to occupy the Hall after Rush had supposedly bought it and had installed some new tenants there. Larner and his friends evicted them and on another occasion, on the 24 Sept 1838, actually seized and occupied the Hall for several hours before the Militia were called out to removed them and take them to the prison in Norwich castle - where they were charged with riotous tumult and assembly. They were bound over to appear at the Spring Assizes in March 1839 when they received 3 months hard labour for simple riot (the lesser charge) - on the understanding that they would make no further claims on the estate - something that Isaac Preston was no doubt very keen to avoid happening. Otherwise, they faced transportation to the colonies. John Larner and his friend then returned to London and kept a low profile - presumably never to be heard of again. By 1840, Isaac and his family had moved into the Hall and for most of the next decade continued there without further concern in this regard.

However, James Blomfield Rush, still the Preston's bailiff, began to be a problem. He had made certain agreements with Isaac concerning land he promised to farm efficiently but again reneged on this and Isaac had to take him to court in about 1847. By July 1848, Rush had been made bankrupt. Moreover, repayment of his loan for Potash farm was due shortly and he had little or no money. He became desperate. Then he remembered the mysterious claims made by John Larner 10 years before. He re-made contact with him in London and was introduced to his cousin - one Thomas Jermy. That name at least pointed towards some basis of the claim for Stanfield Hall. For it turned out that Larner's mother and Thomas Jermy's father were brother and sister - and were both born with the surname Jermy (or one of its many variations). Their grandfather was a John Jermy whom they claimed was the son of John Jermy of Gt Yarmouth, the day-labourer and last survivor of the Gunton branch of the landed Jermy family of Norfolk. As such, he and his heirs would be nearest in blood to William Jermy in 1791, when his widow Frances died. But this family were never aware of when Frances had died and in any case always assumed that one of her Preston relatives, as named in the Will, would have inherited the estate .

By the time they learned the truth, the crucial period of time set by a 'Statute of Limitations' had run out; it was then too late to make a claim - ie after about 1812. But John Larner apparently discovered that if any fraud had occurred in such a case, as he claimed it had, then the Limitation period (usually 20 years) didn't actually commence until after this had been revealed. He thus claimed that the year 1838 fell within this later Limitation period but he didn't have the funds to pursue the matter through the courts. For both he and his cousin were but semi-skilled labourers at best and neither could read or write. No proof of their claimed descent was ever provided and their alleged 'Jermy' family (the name often spelt as 'Jarmany') had actually resided in distant Oxfordshire (as farm labourers) from the time their ancestor, the alleged son of the day-labourer, was barely 18. How and why did he come to move such a distance across the country - in about 1733, if indeed he did ? It was all a bit tenuous and unproved. Yet, how did they come to know so much about William Jermy of Norfolk?

The Murders at Stanfield Hall - 1848.

Nevertheless, Rush decided to hatch a 'cunning plan'. He promised Larner and his cousin Jermy he could put them in possession of 'their' property. He hired a literate secretary in London (one Emily Sanford) and, without her clear knowledge, devised a number of forged documents allegedly designed to switch ownership of the Stanfield properties. These were simply to convince Larner and his cousin. But, said Rush, they had to return to Norfolk at least once to be seen seeking their property again. This they did in early November 1848. This was crucial to his plot. He then forged a number of handwritten Notes allegedly signed by the cousin Thomas Jermy. He had however never seen these. On the night of the murders, two of thes Notes were found in the Hall (those dropped by the murderer) and others scattered about the grounds. They all read: "There are 7 of us out here...and we have come to take possession of the Stanfield Hall property. Signed - Thomas Jermy, the Owner". As mentioned earlier, Rush was immediately suspected and placed in prison very soon. He professed his innocence to the end and tried to make out that some mystery man had approached him a few days before, and that it was him who must have done the evil deeds.

His trial began on 29 Mar 1849 and took 6 days. An early witness called was Thomas Jermy, then a gardening labourer living in south London, aged 67. He was simply asked: "Can you write?" He answered, even briefer - "No Sir". He therefore couldn't have signed the Notes allegedly claiming the estate. But the major prosecution witness was Emily Sanford who had moved in with Rush as his mistress earlier that autumn (Rush's own wife, like his parents, having all previously died in suspicious circumstances, with Rush gaining financially in each case). She spoke of his movements the night of the murders and also about the various documents he had her write out and countersign, etc. in London. Rush tried to defend himself (rather than have a lawyer) and proceeded to give a long rambling speech full of irrelevancies as he cross-examined all the witnesses. It fooled no one and he was eventually found guilty of 'wilful murder' after the jury were out for only 10 minutes. He was sentenced to be "hanged by the neck until dead" at Norwich Castle, and be buried within its precincts'. The judges remarks were exceptionally severe - saying to him "It is a matter of perfect indifference to society at large what your conduct maybe during the few days remaining to you", being as you are "an object of unmitigated abhorrence to everyone". He was hung two weeks later - on the 21 April 1849. A wax death mask was displayed in Madam Tussaud's for many years after.

Because Isaac Preston (Jermy) Snr died moments before his son, the estate passed briefly to that younger Isaac and then, on his death, to his infant daughter. The remaining family soon moved out of Stanfield Hall - wanting never to reside there again. When the daughter was of age, she married into another Norfolk landowning family - the Gwyns and her husband thus inherited the estate. Interestingly, all subsequent Gwyns included the name Jermy in their son's names - even to this day (still fearing claims?). They were of course quite unrelated to that ancient family. The estate was gradually sold off before the war and the Hall was later owned by a local farmer and then by a retired doctor. It was recently purchased by a local business man. So, as we've now seen, Stanfield Hall was once the notorious focal point of a tragic 'ménage a trois' - between Isaac Preston, John Larner and James Blomfield Rush - arising out of William Jermy's controversial Will, and the earlier Isaac Preston's scheming predelictions.

John Larner and Thomas Jermy both died later that century without making any further claims. But John Larner's grandsons did seek publicity in national newspapers on two occasions in the 1920s about the alleged fraud. But no proof was ever forthcoming from the Oxfordshire family concerning their alleged descent from the last (or one of the last?) of the true Norfolk Jermys - John Jermy, the illiterate day-labourer of Gt Yarmouth, allegedly bought off by the earlier Isaac Preston for a mere £20.

The foregoing account is based in part on material also available in the Jermy-Larner section of this website.

Return to the Genealogy Homepage